Yesterday I ran a short workshop for my local writing group. One of our group couldn’t make it, and asked kindly for someone to take notes. I decided to write down my thoughts and share them, with her and with whomever else would like to read them.

Enjoy!

Book Descriptions

I would like to preface by saying the obvious: There are multiple ways to write a pitch, or a blurb, or a book description. Every book is different, and every formula does not work for every book. But this formula, the Four Sentence Pitch, (or the Hollywood Pitch, as I learned it) works for a lot of different books, particularly fiction, particularly novels. It’s a simple structure that can be adjusted and built upon according to your need, and can serve to help you, as an author, to do one of the sometimes more difficult marketing tasks that we have to do: summarize our books in a way that makes readers interested.

But before we go into that, let’s talk about why readers buy books.

Why do readers buy books?

There are lots of reasons for people to buy books. Perhaps one reader needed information on a particular topic. Perhaps another reader had a required reading list that had to be purchased for a course or class they were taking.

We are, for the moment, going to kind of ignore those reasons. They happen, but the thing that will sell novels actually all boils down to one main thing.

Emotions.

A novel is an art form that promises to take a reader on an emotional journey. The emotions are different, of course, depending on genre, and this is something we must be aware of as we are writing our pitch/blurb/book description.

Someone who loves mysteries is hunting for the thrill and satisfaction of solving a puzzle.

Someone who loves fantasy is probably hoping for Wonder, the awe and excitement in exploring a new world different from their own.

A romance reader is looking for, well, romance, which varies in definition from reader to reader.

There are other emotions too: novels take us on journeys where we can experience dread, delight, suspense, grief, despair, triumph, etc. etc.

The reader may not know it, but the reader is looking for that experience. They are looking for that journey.

Your Four Sentence Pitch is taking them on a very, very short version of that journey; giving them a taste of what they will experience if that take it with you. For this reason, the Four Sentence Pitch is something like poetry. We are choosing each word based on the emotional weight it will have for our ideal audience. We adjust sentence structure, length and word order based on that emotional journey. It can sometimes take a long time to write one, and then there may be revisions.

That’s okay. We have time to get it wrong, and we have time to get it right.

The Purpose of the Four Sentence Pitch

There are two main reasons for writing a strong book description.

- To get readers to start reading your book by giving them a hint of the emotional arc of the book, and a taste of the author’s writing style.

- To convince readers who will not enjoy your book to put it down and choose a different book, by giving them a hint of the emotional arc of the book and a taste of the author’s writing style.

A good book description is as much of a filter as it is an invitation. A good book description will help a reader who is looking for a particular kind of book to know, immediately, whether or not your book is for them. Let’s keep this in mind as we’re writing our own book descriptions.

Basic Structure of the Four Sentence Pitch

The First Sentence: Establish character and setting.

The Second Sentence: Further develop character and setting, and establish conflict and stakes.

The Third Sentence: Heighten the stakes and conflict, hint at the twist, and give away the ending without giving away the ending.

The Fourth Sentence: A very clear and concise description of your book, covering theme, THIS + THIS description (more on that later), title, and essentially sealing the promise of what this book is.

There is room for adjustment in all of these. In general, this is a strong formula to follow, and if we adhere closely to the order and the creative boundary of 4 sentences, it can help us understand our own work, and then, crucially, be able to share it with others.

When should I write my Four Sentence Pitch?

That’s going to vary based on how the author’s brain works. For me, primarily a freewriter, I tend to write my pitches/book descriptions after I finish the novel, because I typically do not know what my book is about until I have finished. For others, who perhaps are more plot-oriented, they might be served better by writing the Four Sentence Pitch before they write their novel, as touchstones or pillars for what they are trying to make their book become.

Each of us has to figure that out for ourselves. Suffice it to say, the answer to the question of ‘When should I write this?’ is basically, ‘Whenever works best for your process.

Moving on.

First Sentence: Establish Character and Setting

Readers need some context. And readers want to know who they are going on this journey with. Just like in your novel, they need to be grounded in setting, and have a person that they can identify with, relate with, or otherwise enjoy going on the journey with for whatever other reason. These are the first clues for your reader about genre, by the way, and are pretty important to include.

Is your character a young farmboy in a mystic land of adventure?

Is your character a hardboiled detective in a city full of crime and corruption?

Is your character a shy teenage girl who has just moved to a new town and school?

Is your character an up and coming fashion writer who just got hired at a major fashion magazine in a bustling metropolis?

You don’t have to explain everything. You can’t. Find the essence, the thing of most importance, and go with that. And if you have multiple main characters… well, you’re probably going to need to adjust this formula to fit that, or find another formula. This formula tends to work best with a single character, but like I said at the beginning: all of this is adjustable.

Second Sentence: Further develop character and setting, and establish conflict and stakes.

For Western style storytelling, as in, the cultural West (US, Europe, etc.) conflict and stakes are a key part of story. I imagine that this formula might not work as well with other storytelling traditions. But within the Western storytelling tradition, your reader wants to know what the obstacles are for your character, within the setting, and what the stakes are. This gives more clues to the reader about genre and emotional arc.

Does the young farmboy stumble upon a magical sword that is the only key to defeating the dark lord?

Does the hardboiled detective accept a case that he knows is a really bad idea?

Does the shy teenage girl get forced to join the drama club for… I dunno, plot-convenient reasons?

Does the fashion writer immediately clash with the powerful owner/mogul of the fashion magazine… who for whatever reason, is also immensely attractive?

You can see some of these are outside of my genre, and someone who writes those genres could probably do better at scenario. Regardless, the point is made.

Third Sentence: Heighten the stakes and conflict, hint at the twist, and give away the ending without giving away the ending. Oh, and also, keep talking about the theme of your book too, if you can.

This sentence may be the most difficult to write, but it is vital to this formula. And yes, there is a lot of information we’re packing into this sentence.

If we get it right, it’s amazing, and it will get your reader very interested in reading.

Heighten the Stakes

In order for the character’s triumph to matter, things need to be both difficult and important. And yes, ‘difficult’ and ‘important’ are subjective. They will vary based on the genre. The difficult thing in the young adult coming of age story will not match the difficult thing in the hardboiled detective story. But in either of those stories, if they succeed without any real effort, without any real struggle, we will be bored.

Boredom, by the way, is not an emotion that sells books. Quite the opposite; it is the main emotion that prevents books from selling when all other factors (money, opportunity, etc.) are in place.

So we show the stakes rising, and the conflict rising with them. Perhaps the young farmboy realizes that the only sword that can destroy the Dark Lord will also destroy himself if he uses it. Perhaps the hardboiled detective crosses the most powerful crime boss in the city, who puts a five thousand dollar bounty on the detective’s head. Perhaps the shy teenage girl, who was only wanting to be a stage hand, gets put on stage by the bombastic drama teacher. And perhaps the reasonably attractive fashion writer has… well, whatever conflicts that romance stories have. I don’t know. Make one up, it’ll be more on the nose than whatever I’m gonna come up with right now.

But we have to do it pretty concisely, because we’re also trying to do two more things in this sentence.

Hint at the Twist and Give Away The Ending Without Giving Away The Ending

There are twists in books. And readers love twists. And so, if you have a twist, a reversal of fortune that spells disaster for your reader, this is the place to hint at it.

Do not give away the twist.

Just a hint.

And this is a hard thing to do. For sure. Because we have all watched those previews for movies that give away the entire movie in the preview. But if we, the writers, can hint that there is something unexpected which the reader will experience, that is a promise to your reader that they will want to have fulfilled.

Related to this promise is ‘giving away the ending without giving away the ending’.

Endings are tricky things. Get it right, and you win. Get it wrong, and it ruins the entire journey that preceded it. It would be like going on a beautiful hike, walking among the aspen trees and listening to the birds singing, only to fall into an open crevice of molten magma right at the end.

There are stories that end that way. I don’t like them, and your readers probably won’t either.

So, in the Third Sentence of our Four Sentence Pitch, we are going to give away the ending. Not in the details. Just in the emotions. Because we are letting our readers know the destination of the emotional arc of this book. We are letting them know what kind of satisfaction is awaiting at the conclusion.

Obviously, the wrong way to do this is to simply say outright the factual nature of the twist and the ending.

“The farmboy Craig discovers that the sword was actually his true love transformed into a sword from the beginning, and has to decide between freeing her and defeating the Dark Lord, but then he realizes that by breaking the enchantment over the sword in the right way, he undoes the power of the Dark Lord over the entire land, and frees his one true love, and it’s super emotionally satisfying!”

Well, okay. That’s technically one sentence, but now we don’t really need to read that book, as awesome as the 240,000 word version of that would probably have been.

Maybe better: “But the Dark Lord has plans within plans within plans, and the mysterious weapon that could end his reign forever may also spell doom for the soul of the one who can wield it.”

Maybe better. If I was writing the whole pitch, though, I might make that the second sentence. Or I might leave it as the third sentence, but split it and add more of a hint at the ending. And I could spend a couple of hours fine-tuning pitches for multiple books I’m not going to write… but in the interest of time, and in the interest of actual books that I actually have waiting for me to write, we’re moving on.

Fourth Sentence: A very clear and concise description of your book, covering theme, THIS + THIS description (more on that later), title, and essentially sealing the promise of what this book is.

And here is the clincher. This sentence is much more cut and dried. You are telling them what you already told them, in plain language, so there are no mistakes.

There are a few ways you can structure this sentence, but one way that works pretty well is:

TITLE + WHAT THE BOOK IS + THEMES + THIS & THIS

Something like this, flavored to genre:

“The Tragedy of Darth Plagueis the Wise is a political dark fantasy tale of unchecked ambition, the desperation of power, and the meteoric downfall of the proud for fans of Oedipus Rex and Dune.”

You’re reinforcing in plain language what your story is. Along the way we have been laying it out in pretty clear hints, and now we are putting the label on the tin. You are telling them the title. You are telling them the genre. You are telling them the payoff. You are showing them a couple of other well-known works that if they liked, they’ll probably like yours too.

Typically, we will choose titles that are well-known, and interesting in the combination. Obscure titles, while they may be very descriptive, do not spark recognition and familiarity. The entire point of using a This & This formula is to spark recognition, familiarity, and interest. Use titles familiar to readers of the genre you are writing in.

It is also okay not to use This & This. Totally okay.

By this sentence, the fourth sentence, it is important that we know what our story is, or that we know for certain what our story is going to be when it is complete. Which is why I don’t write book pitches until I have finished my books; I don’t know what they really are until they’re done.

Your process will differ. That’s okay.

Okay. I haven’t covered everything, and I haven’t yet given examples. So let’s get into some examples. I’ll use my own work, and you can see where I followed the formula and where I departed from it. I’ll tell you up front: most of these break one or another of the rules, because these rules are here to serve us, we’re not here to serve the rules.

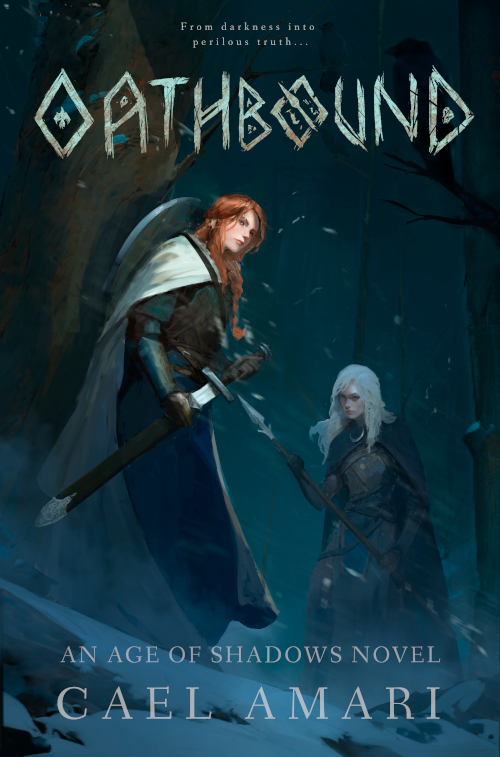

Four Sentence Pitch: Oathbound

Life is short is Signe’s village. Monsters and undead infest the unforgiving mountains, and a brutal winter is prowling at the door. But when her closest friend is murdered in secret, Signe must undergo a dangerous journey in order to find the truth — and exact justice for the dead.

Sword’s justice, if needs be.

Yet sometimes justice is not what one finds at the end of an oath of vengeance, and sometimes, it takes more than a blade to ensure the dead are truly at rest.

Rooted in a Dark Age inspired world, with nods to Old Norse, Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian legend, OATHBOUND is a standalone dark fantasy novel.

All right. Let’s use some colors to show what I’m doing here.

Life is short is Signe’s village. Monsters and undead infest the unforgiving mountains, and a brutal winter is prowling at the door. But when her closest friend is murdered in secret, Signe must undergo a dangerous journey in order to find the truth — and exact justice for the dead.

Sword’s justice, if needs be.

Yet sometimes justice is not what one finds at the end of an oath of vengeance, and sometimes, it takes more than a blade to ensure the dead are truly at rest.

Rooted in a Dark Age inspired world, with nods to Old Norse, Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian legend, OATHBOUND is a standalone dark fantasy novel.

So, the first sentence, in green, I split up into two sentences for effect. We’re establishing up front the setting (more than the character, honestly). I’m making it clear that this is not our world, but a different one. There are monsters and undead in the mountains, which lets the reader know that this is not historical fiction, as most people do not believe in monsters or undead. I use words like ‘infest’, ‘unforgiving’, ‘brutal’, ‘prowling’ to establish tone, as a part of setting.

I let you know that Signe is the person this story is about. And that’s pretty much it. Maybe in another genre I would spend more time talking about her, but as this is fantasy, I needed to make sure the setting was established well.

Then, second sentence, in yellow, I drop the conflict. Her best friend has been murdered. And we get to know a little more about Signe and what she needs and wants: justice for her friend. Vengeance, really, but that line gets blurry. And she has to take a dangerous journey. And there is a sword involved.

I’m using more tone/emotion words: ‘secret’, ‘dangerous’, ‘exact’, ‘dead’. And again, I split this into two sentences, because the rules serve us, we do not serve the rules.

Third sentence, in orange: I let you know that there is a twist. Sometimes oaths of vengeance don’t lead to justice. Sometimes it takes more than a blade to ensure the dead are at rest. Which hints at the theme and the thesis of this book, the twists (there are more than one) and at the ending.

No, I won’t spoil it for you. Just go buy it and read it. :]

Fourth sentence in Red: I tell you what the book is. Plain and simple.

There was a version of this description where I referenced Beowulf and The Lord of the Rings, if Eowyn was the hero. In a future edition of this book, I might retool this decription to include that. For now, this version is serving my purposes.

Again, the rules serve me, I don’t serve the rules.

A Song for Fallen Troy Book Description

Eirene, youngest slave in the victorious House of Menelaus, longs to know more of her homeland, Troy.

The only person who will tell her is Helen, the fatally beautiful cause of the Trojan War, and Helen can only tell it in whispers, away from the ears of the Spartan King and his house full of those who revile her.

But Eirene needs more than the Queen has power to give, so much that when a stranger full of song comes to visit, even deadly peril cannot stop Eirene from seeking the lost music of fallen Troy, and the words of mourning that someone sings in her dreams.

A Song for Fallen Troy is a short novel about grief, redemption, and the aftermath of war, set in mythological ancient Greece.

This one follows the formula much more closely. I probably should have put it before Oathbound, but hey, I’ve got books to write, so it came second. :]

First sentence: we establish who Eirene is, and her setting. If you have read The Illiad, or if you are familiar with the story of the Trojan War, you know who Menelaus is. If not, then it is still established that Eirene is a slave, and you know what she wants, more than anything.

Second sentence: The stakes are established. Troy is no more, and it is dangerous to bring it up. Especially for a slave. Even the queen, Queen Helen (yes, that Helen) does not dare to talk openly of it, for fear of what will happen.

Third sentence: We raise the stakes, we hint at the twist and the ending, and at the payoff. You know before reading this book that Eirene will face deadly peril over the knowledge of where she came from… and more, which is there but not so spelled out, will have to act with courage in order to do so.

Last sentence: I let you know what this book is about. And the genre. And the title. Again, I do not use the ‘This & This’ formula… but my books are kind of odd.

Remember, the rules serve us, we do not serve the rules.

Throughout the description for A Song for Fallen Troy, I selected words that had the energy of the story I am trying to describe: ‘longs’, ‘fatally beautiful’, ‘whispers’, ‘stranger full of song’, ‘deadly peril’, ‘words of mourning’, ‘dreams’, ‘grief’, ‘redemption’, ‘the aftermath of war’.

The reader will hopefully know that this is not an action-packed thriller with explosions and gunfights. Nor is it a comedy of errors, or a love story. This is a painful story, painful like washing out a wound and binding it with salve.

Another note about this book description: typically speaking, I try to keep names to a minimum. There are a lot more named characters in Oathbound, really important ones. But I name only Signe in that description, because more would only split focus.

In A Song for Fallen Troy, I named two additional characters. Menelaus, and Helen. These are very old and well established characters. They’re older than many Bible stories by hundreds of years. My intention in using these names was to spark familiarity in those who know Greek myth. It would be a little bit like name-dropping Robin Hood in a story about medieval England, or name-dropping King David in a story about the ancient kingdom of Israel.

If Menelaus and Helen were not so well known? I probably would not have used their names. We only have so much space to work with in a book description.

In Conclusion

Once again, remember, there is more than one way to do this. And I am not in any way a 10,000 hour expert. I do it well enough, but I get better with practice, and you can too.

I’d suggest to fellow Students of the Book Blurb that hours spent in our homes or local libraries or local bookshops analyzing the back cover matter of the best books might serve us well.

Thanks for reading. :]

Leave a Reply